Maternity Portraiture by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun:

How Eighteenth-Century Art Mirrored Changing Paradigms in Child-rearing Practices

(History of Art undergraduate paper, presented at January 2012

UVic Intersec+ions in Art" Symposium).

(By Holly Cecil)

| Click on any image to enlarge: Self-Portrait with Daughter, Julie (1789) by the French painter Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun captured my imagination the first moment I saw it. Having a daughter myself, of a similar age to Julie in the painting, I immediately identified with the poignant bond between mother and child this image so warmly evokes. We are witness to a suspended moment in time in the private lives of this pair, the daughter spontaneously embracing her mother before skipping off to play outside. It is one of life’s precious moments that mothers treasure. And yet these two are not oblivious to the viewer, they turn to face us as if to emphasize the meaning in their image. We are given few hints as to what that might be: the simple harmony of the triangular composition, the understated background, the absence of cluttering visual symbols which painters use to infer a hidden narrative, leave us with no alternative but to see them simply as they are: a mother and daughter, embracing. Could this be the message? An in-depth study of this artist revealed the fact that her many maternity paintings coincided with—and indeed embodied— much-needed social reforms in the child-rearing practices of pre-Revolutionary France. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Daughter, Julie, 1789, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. |

|

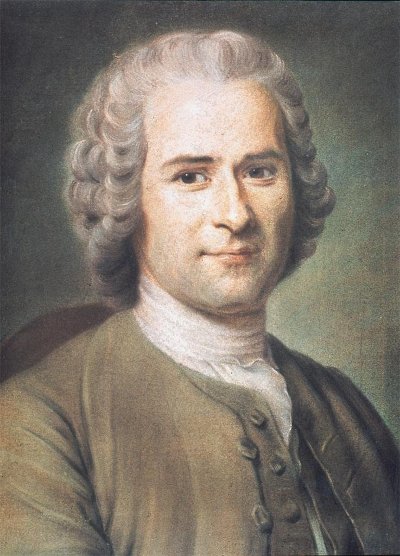

This paper will explore the intersection of art and social revolution in late eighteenth-century France, as they relate to the plight of children and the cultural traditions which impaired them. I have drawn primarily on the French social historians Philippe Ariès and David Hunt’s in-depth examinations of children through the Early Modern period. The much-needed reforms in child-care were spearheaded by Enlightenment writers such as the renowned Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). In addition to being an accomplished composer of music, during the years he resided in France Rousseau published extensive treatises on education, equality and social reform, which were immensely popular throughout western Europe, particularly France and England.1 He was not alone among Enlightenment writers in promoting humanism and improved children-rearing practices, being influenced by the English “Father of Liberalism” John Locke, and joined by reformers such as François Fénelon who wrote Treatise on the Education of Daughters . Rousseau believed that “good education flows from an understanding of the nature of children and the way their minds work,”2 and proposed that “children should be brought up as one might cultivate a tree: without pruning it, or forcing it to grow up a frame, but with the most constant attention to help ‘Nature’ produce a full, strong tree.”3 What is critical to my study is Rousseau’s emphasis on the importance of nurturing familial bonds in order to create a functional society. He decried the prevalent tradition of employing wet-nurses for infants, instead advocating that women breastfeed their own babies. His social discourses find artistic expression in Vigée Le Brun’s maternity portraits— including her own self-portrait with her daughter, Julie (whom it is believed she named after the heroine in Rousseau’s romantic novel Julie, ou Nouvelle Hélöise, the equivalent of a runaway bestseller in its day4). To view how art reflected changing attitudes toward children, I will move rather quickly through images by artists from the sixteenth- to eighteenth-centuries, both within France and from other European countries. These serve to illustrate the evolution in portraits of mothers and children, from their early expression in religious images of the Madonna and Christ child, through genre paintings by Greuze and other artists which exposed child-rearing practices, and to their final independence as secular portraits of maternal love. |

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Portrait of Jean Jacques Rousseau. Pastel, c. 1700s, 18" x 15", Geneva (Switzerland). Musée d’art et d’histoire. ArtStor. |

|

The life of Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun is a fascinating study, for not only was she counted among the few female artists of her age to find professional success, but her life reflects the tumultuous turns of fate Europeans were subject to in the decades spanning the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars. She achieved early notoriety and an established career as a pastel portraitist of Parisian nobility at the young age of 15.5 Soon thereafter she became court painter to Queen Marie- Antoinette and claimed the rare feminine achievement of being elected into the male-dominated Academy in 1783. Because of her close association with the queen, in order to save her own life she fled France on the very night the monarchs were taken prisoner in 1789. She would spend the next fifteen years alone in exile with her daughter Julie. Invited to the courts of Rome, Naples, Vienna, St. Petersburg and London by reason of her artistic reputation, she was able to support herself and her daughter through portraiture commissions by Europe’s noble families. It is one of her life’s ironies that without the impetus of being forced into exile, the art world would not now be heir to her outstanding oeuvre of pan-European maternity paintings. In her long career she created approximately 900 works of art, 600 of these paintings,67 and I will especially examine those maternities in which an unprecedented affection between mother and child reflect changing attitudes in parenting. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait, 1790. Oil on canvas, 100cm x 81cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. |

|

In order to fully appreciate the reforms in maternal relationships that Vigée Le Brun’s paintings embody, I must first explain the child-rearing practices then common in France. The painter’s early life will serve to illustrate the precarious social existence of children in this period. As was customary among the middle- and privileged classes, Elisabeth was sent after her birth to reside with a peasant wet-nurse. In this farmhouse outside Paris she spent the first five years of her life. She would have grown up hardly knowing her parents, for their sixty-five-kilometre journey over bad roads would have allowed for few visits. Such rare interaction with her birth parents we may imagine as we view this painting, titled The Visit by the Belgian artist Basile de Loose. The well-dressed woman to the left may well represent Elisabeth’s mother, Jeanne, a Parisian hairdresser, and the well-dressed gentleman to our right her father, the mildly successful pastel portraitist Louis Vigée. Yet they would have appeared as virtual strangers to the child, as her affections would have long since been transferred to the rural wet-nurse and her husband, because of the bonds that are woven day after day through infant care and feeding. The wet-nurse is shown presenting the baby to her parents for inspection, and her rustic husband sits off to the far left. One would hope that the infant might have a chance to build those lost connections with her birth parents upon returning home at a later age, but when Elisabeth’s time with her nurse was completed at age five, she soon found herself enrolled in the convent school where she resided until her eleventh birthday.”8 What would be the emotional impact on a young mind, of not being allowed to reside in his or her own home for the first eleven years of life? Many years later the artist would record in her memoirs that when she was at last allowed to return home at age 11 she was overjoyed at not having to leave her parents ever again. Yet within a year her father would be dead, and the opportunity to make up for those years apart from him irretrievably lost.9 |

Basile de Loose (1809-1885), The Visit. |

|

The practice of abandoning offspring to distant care-givers, common for that period, we may today see through the modern lens of child welfare, and label as abandonment or emotional child abuse. Perhaps worse than being orphaned, would be the eventual realization in the young child’s mind that “my parents live, but they don’t want me in their home.” In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, once a mother had fulfilled her task of successfully birthing an infant, the subsequent nursing and care of her baby were considered the work of servants. This image by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1780) depicts a scene turbulent in both chaotic elements and emotional implications. At the heart of the composition is the mother’s parting embrace with her newborn infant, as the hired wet-nurse who already holds it prepares to convey it to their village in the donkey’s basket, which her husband is making ready. The engraving’s subtitle, Emotional Privation, speaks to the unnatural severing of one of nature’s strongest bonds: that of mother and child. The many discordant elements in this image—such as the dogs threatening the children in the foreground—foreshadow the infant’s uncertain future. For Greuze this topic would have been a personal one, as his own two daughters were placed with a wet-nurse at birth.10 |

Greuze, Jean Baptiste (after), Depart de Nourrice (Emotional Privation). Engraving, 1780, Collection des Espampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

|

This is Nursemaids (1769), again by Greuze. His illustration of social issues in genre painting coincides with the cultural debate that gripped public opinion in the mid-eighteenth century, between maternal nursing and so-called ‘mercenary’ nursing. This is not the earlier de Loose image of the charming rustic cottage of the wet-nurse we imagined being visited by the Parisian parents. Here Greuze shows the cramped and dirty conditions children were often raised in, strewn with unwashed cooking pots, laundry and a cat sleeping in the baby’s cradle to the left. The slightly tilted alignment of the room contributes to the unsettling impression that the children’s fate is uncertain. The sullen expression of the nurse on the right confirms society’s suspicion of their sometimes mercenary attitudes, which might calculate the death of their own or another’s child through neglect as merely making way for another paying customer. Despite a campaign against wet-nursing, it persisted among all but the poorest classes, and more wet nurses were employed in France than in any other country.11 Common these standards might have been, but tragic in terms of infant mortality in which a staggering “nearly 80 per cent of infants died in their first year, the vast majority of which at their nurses’.”12 13 Initially I could not believe this devastating statistic, but found it corroborated in numerous historical demographic sources which confirmed that, particularly in the larger cities like Paris and Lyon, only one in five infants could be expected to outlive their first year.14 Even the lucky ones who survived would remain on precarious footing in the years that followed, at the mercy of childhood diseases and further neglect. It is considered that the preliminary oil sketch of this painting was first conceived by Greuze on one of the visits to his infant children in Champigny, half a day’s journey by coach from Paris.15 In showing us the squalor of the children’s environment and their dark-humoured nurses, Greuze was not only addressing the conditions that farmed-out children were subject to, but also the implications for their development as emotional and social beings. If “the environment makes the child and the child makes the man,” then the moral decay in the social fabric of the nation began here in their infancy, in the practice of abandoning children to wet-nurses.16 In his 1762 treatise on education, titled Émile, Rousseau underscored that the health of the nation began here in the formative years of its subjects, and that “a true project of social reform should begin with mothers.”17 |

Greuze, Jean-Baptiste, Nursemaids, 31.7 x 40 cm, Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, Missouri, USA. |

|

Greuze’s companion piece to Emotional Privation (Depart de Nourrice) is Retour de Nourrice (Back from the Wet Nurse) from 1780. This image completes the circle of the child’s journey, returning it to its familial home, which often occurred by the age of four. The seated mother seeks to welcome her child with open arms, but the child shrinks away from her and instead turns to the solace of her nurse behind her. The historian Bernadette Fort explains in her paper “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing in Eighteenth-Century France,” that the mother has thus suffered multiple losses: both “physically at birth and emotionally when he returns, and the irreparable deprivation of motherly affection for the child in the crucial years when a lasting bond could be established.”19 The image emphasizes not only the child’s loss of parental affection in the years since its birth, but also the mother’s loss of her child’s love: by abandoning her to a wet-nurse, the child understandably has transferred her affection to the surrogate. The wet-nurse’s husband carries the child’s bed into the house, but does it mean he or she is home to stay? As we have seen in the case of Vigée Le Brun, this return might be only temporary, as her subsequent enrolment in a residential convent school attests. Boys were more often sent away to school or apprenticeship by age seven.18 |

Greuze, Jean Baptiste (after), Retour de Nourrice, (Back from the Nurse). Engraving, 1780, Collection des Espampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

|

Another depiction of parental estrangement is Etienne Aubry’s Farewell to the Wet-Nurse (1776). For several years the only care the infant knew was given by the surrogate parents on the left; understandably the child is reluctant to be withdrawn by its birth mother who is already mounted on the donkey, ready to leave. This emotional tearing contrasts greatly with the aloof indifference on the part of the baby’s father standing off to the right. Rousseau warned parents that, “the long absence of a child whom the father has seen but for an instant, weakens, and at length annihilates paternal sentiment, and parents will never love a child sent to nurse, like that which is brought up under their eyes.”20 |

Aubry, Etienne, Farewell to the Wet-Nurse, 1776-1777. Oil on canvas, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA. |

|

With a better understanding of the formative influences in Vigée Le Brun’s childhood, let us advance forward in her life to note her marriage in 1775 and the birth of her daughter in 1780. In 1786 she painted this self-portrait with her daughter Julie at age six. Similar to the self-portrait we saw when Julie was nine, she here again used a three-quarter length format, the two figures appearing close to the picture plane which invites an intimacy of beholding on the part of the viewer. The effect of the uncluttered composition and understated background serve to focus our attention directly on the figures’ tender embrace. The richness of their affection is complemented by the luxuriously painted fabrics of their costume and the upholstery beneath them. The sensitively rendered hands of the mother enfolding her daughter emphasize the intimacy of their bond and the mother’s emotional investment in her progeny. This is the poignant summation of everything Rousseau hoped for. We noted how Greuze used negative imagery to warn the viewer of the hazards of wet-nurses; Vigée Le Brun instead portrays the positive benefits to both mother and child when she invests in the raising of her own daughter. The love and maternal joy shining from the painter’s eyes testify to the emotional rewards which only a mother who asserts a primary role in her daughter’s upbringing can claim. This painting thus becomes a direct embodiment of Rousseau’s parenting ideals, using the visual language of art instead of text.21 When this painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1787 a contemporary reviewer wrote: "Madame Le Brun, by painting herself holding her child in her arms, shows how ... art can serve mankind better than the demonstrations of a moralist.”22 |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Daughter, Julie, 1789, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. |

|

This maternity by the artist is Madame Rousseau and Her Daughter (1789), incidentally not the family of the philosophe Rousseau but of Pierre Rousseau the architect. Again the intimacy of the three-quarter length portrait draws us in to the gentle warmth between the two figures, the mother’s arm enfolding her daughter and their joined hands inferring a trust and affection belonging to engaged parenthood. Unlike Julie in the previous portrait, this daughter looks away, but the mother engages the viewer with a direct gaze which fully owns her maternal role. Consider the clothing of the girl and how it is designed for freedom of movement. Rousseau’s discourses advocated a return to nature, and these portraits reflect a concurrent change in fashions. Vigée Le Brun was renowned for arranging her aristocratic mothers in more relaxed costumes with draped shawls, and dispensing with the wearing of powdered wigs for more naturally arranged hairstyles with loose turbans. Her memoirs state that when her female sitters left her studio for the opera wearing the styles she had conceived, they began to set fashion trends and be copied more widely.23 The gorgeous moss-green and wine-coloured silks in Madame Rousseau’s garments illustrate her privileged position in society, but they are not the stiff and unnatural gown styles in which we usually picture Rococo women. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Madame Rousseau and her Daughter, 1789. Oil on canvas, 1.16 x 0.87 m, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. (Wife of Architect Pierre Rousseau) |

|

Here is a contrast shown by the artist Drouais: Boy In Blue Building a House of Cards, With Two Girls (c. 1760). It is difficult to conceive that prior to this period, the conception of childhood as a unique phase of life, of children as having needs and methods of learning different to adults, did not exist. Once children had survived the dangerous phase of infancy and early childhood, they were dressed as adults and effectively entered the adult sphere.24 Here the children’s movement is limited by the wearing of corsets, and the style of their ornate fashions is hardly distinguishable from those of adults. These constraints were hardly conducive to the youthful proclivity for exercise and freedom of movement. By contrast, the natural child proposed by Rousseau “wears comfortable clothing unfettered by corsets (an idea that revolutionized children’s dress) and is allowed spontaneity of imagination as well as physical movement in his exploration of nature.”25 |

Francois Hubert Drouais, Boy In Blue Building a House of Cards, With Two Girls, 1760. Oil painting. |

|

Continuing the theme of constricting garments, Madonna with the Swaddled Infant by Albrecht Durer illustrates the critical issue of swaddling, joining the topic of wet-nurses as the two traditions of infant impairment that Rousseau most wished to see abolished. This image also serves as a comparative view of earlier maternity images, which prior to the Enlightenment existed primarily in the domain of religious narrative.26 I was not familiar with “swaddling,” the word calling to mind perhaps images of a nativity scene with Mary wrapping the Christ child in warm blankets, a fiction which is in fact far from the truth. In the medieval and early modern period, the practice meant stretching an infant out with her arms straight at her sides, and wrapping her entire body with a band of cloth so tightly that she couldn’t move, and with only her face visible. She would barely have room to breathe, and was laid on her side so that any fluids could drain from her mouth, for she was not free to turn her head on her own. This swaddling was only ever temporarily removed to clean the baby. The effect this had on infants may be gleaned from an account by a mid-sixteenth-century French doctor, Simon de Vallambert, who suggested that “if an infant cried excessively, one could unswaddle him, and massage and move his limbs, for that often causes the crying and the screaming to stop.”27 Rousseau appealed to the humanity of mothers who abandoned their children to such treatment at their wet-nurses, for the freedom it gave them to enjoy their husbands and an urban social life: “These gentle mothers, having got rid of their babies, devote themselves gaily to the pleasures of the town. Do they know how their children are being treated in the villages? If the nurse is at all busy, the [swaddled] child is hung up on a nail like a bundle of clothes and is left crucified while the nurse goes leisurely about her business. Children have been found in this position purple in the face, their tightly bandaged chest forbade the circulation of the blood, and it went to the head; so the sufferer was considered very quiet because he had not strength to cry. How long a child might survive under such conditions I do not know, but it could not be long.”28 |

Albrecht Dürer, Madonna with the Swaddled Infant, 1520. Engraving, 44 x 97 mm, The Illustrated Bartsch. |

|

If the practice of swaddling had such an effect on infants why did it persist? Historical proponents of swaddling believed the practice helped ensure that the infant’s limbs and torso would grow straighter, a conjecture which was disproved through increased travel to other countries where swaddling was not practiced. Modern child studies confirm gentle swaddling is an effective strategy for triggering a calming response in the child, replicating their confined environment in utero, but even as an infrequent practice it is not recommended after four to six weeks of age. Beyond that, it can prevent important motor and neural development. A threefold increase in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is recorded among swaddled babies left in the prone sleeping position.29 The Florentine Mannerist painter Bronzino’s Portrait of a Baby Boy (c. 1540) illustrates the prevalence of swaddling throughout Europe in this period, and the implied apprehension of freeing a baby to develop according to its own natural processes.30 Rousseau writes, “The child has hardly left the mother’s womb, it has hardly begun to move and stretch its limbs, when it is deprived of its freedom.” “Civilised man is born and dies a slave. The infant is bound up in swaddling clothes, the corpse is nailed down in his coffin. All his life long man is imprisoned by our institutions.”31 |

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of a Baby Boy, 1540-1549. Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 26 cm, The Walters Art Museum. |

|

Traditional swaddling dictated that by around the fourth month, the infant would be re-wrapped to free its arms, but his legs and torso continued to be bound, night and day, for up to a year.32 This is illustrated in the French artist Beaubrun’s painting of Louis XIV and his Wetnurse (1638). When one considers a baby’s first year of life, and that normal motor development including grasping, kicking and crawling is crucial to neural development in the infant brain, impeding that through restrictive swaddling would be certainly detrimental. The high fatalities of infants, swaddled and often left to hang from a nail on the wall of their wet-nurse’s cottage for extended periods, were brought to public awareness through Rousseau’s reforms. Clearly, parenting had gone down the wrong road. If the age of Enlightenment was about asking, “How can we live a better life?” then child-rearing practices were not exempt from the debate. European ships now circled the globe, and brought back accounts of exotic cultures and their social practices. In his educational treatise Émile, Rousseau publicized the fact that other nations who did not practice swaddling were not only unharmed, but they grew straighter than those nations who did: “Where these absurd precautions are absent, all the men are tall, strong, and well-made. Where children are swaddled, the country swarms with the hump-backed, the lame, the bow-legged, the rickety, and every kind of deformity. In our fear lest the body should become deformed by free movement, we hasten to deform it by putting it in a press. We make our children helpless lest they should hurt themselves.”33 Child-rearing practices that may have been convenient for carers were often fatal for the infants themselves, as we have seen in the death-rates which in urban centres such as Paris and Lyon exceeded eighty percent in an infant’s first year of life. While childhood diseases and hygiene may partly be to blame, death-rates were never so high in other countries as in France where mercenary nursing and swaddling were commonplace. To seek a cause for these death-rates, an issue of equal concern is the primal human need for touch and affection, which is well-documented.34 |

Charles Beaubrun and Henri (the Younger), Louis XIV and his wet-nurse (Mme Longuet de la Giraudière), c. 1638, 84 x 68 cm. Oil on Canvas, Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. |

|

Like our primate cousins, as a species we evolved for millions of years investing in close parent-infant relationships. We differ from other mammalian species such as ungulates whose adaptations allow their newborns to be able to get on their feet and run from predators within minutes of birth. The increased brain-development requirements of the infant primate, including humans, necessitate its total dependence on maternal care for food, mobility and stimulation for at least the first year of its life, and to a lesser extent for many more years. The relatively recent phenomenon of the “civilizing” of nations and their social and infant-rearing practices cannot override millions of years of evolutionary adaptation. The last thing the human infant wants is to be shut away in a charmingly-decorated nursery and left to cry “for its own good,” as parenting manuals of the early twentieth century advocated. For optimum development the human infant expects only what its predecessors have expected for millennia: the warmth of constant contact within mother’s embrace, the physical nourishment and emotional bonding of breast-feeding, and to be physically free to engage with their visual and physical environment without constraint. Following his publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, Charles Darwin initiated the field of evolutionary psychology by searching through our species’ mammalian history for the origins of human behavior. In his (1872) book The Expression of the Emotions, comparing the behaviour of primates, other mammals and tribal peoples from all over the world, he argued that “human affection, sympathy, parental love, [and] morality ... had gradually developed from a primate base.”35 Questions of how to best optimize child development are issues still very current today, and have given rise to progressive treatises such as The Continuum Concept by Jean Leidloff, which inspired a revolution in so-called “attachment parenting” now practiced by families—my own included. Within the limitations of her day, Vigée Le Brun’s portraits of mothers and children gave form to what then was essentially an equivalent revolution in attachment parenting. |

(Photographer Unknown), Chimpanzee mother and baby |

|

To examine how Vigée Le Brun’s maternity portraits express this socially-important topic of touch, consider her Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rougé with Her Two Sons. The sumptuous colour in the rich fabrics, their shimmering surfaces, the soft light accentuating the figures’ pure skin and rosy cheeks and lips, all underscore the emotional richness in the painting. I enjoy the fact that in this composition no one’s hands are kept to themselves but are employed in a caress of the person nearest them: the Marquise de Pezay’s left hand rests affectionately on her friend’s shoulder, as her right hand gestures to the youngest boy—it is as if we have happened upon them in the park and she is in the act of introducing us to them. As small children often do when being introduced, the youngest boy retreats to the security of his mother's lap. The elder son embraces his mother; her left arm returns that embrace and her right hand rests on her friend’s leg. This circle of freely-bestowed physical affection is conspicuous by its comparative absence in the formality of most family portraits prior to this period. Contrasting the earlier Drouais portrait of corseted children, these boys instead emulate Rousseau’s “natural child,” wearing comfortable clothing allowing freedom of movement. What is also significant is that the artist does not employ Baroque narrative techniques and depict her sitters as classical characters such as Venus or Juno, or the children as cupid or putti, adding what the French historian Lesley Walker calls “allegorical freight.”36 By stripping away any elements of narrative, as in her prior self-portraits with her daughter Julie, the artist lets us see these individuals purely for who they are: mothers and children. The medium is the message. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rouge with Her Two Sons, 1784. Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. |

|

The success of Vigée Le Brun’s maternités at the Paris salon did not go unnoticed by the French government, who commissioned her to paint Marie-Antoinette37 in an attempt to salvage the queen’s tarnished reputation among the French people. The artist drew on the Christian iconographic tradition of altar-pieces of the Holy Family and presented the queen as “Procreator of the Children of France.”38 Despite the richness of the costumes, the silks, the velvets, the tapestries, in this work we are not shown the open warmth and affection evident in Vigée Le Brun’s other maternités; but perhaps this can be explained by the family having been recently bereaved. The Dauphin to the right gestures to the empty basinette of the queen’s recently deceased infant daughter Sophie-Helene-Beatrix. As she died only two months before the painting’s completion, she may have originally occupied the cradle but been painted out.39 The queen’s eldest daughter leans affectionately against her mother, who in turn holds the infant Duc de Normandy in her lap. This painting would not go on to achieve the aims intended by its commission, for the only figure in it who would be left alive by the end of the Revolution was the eldest daughter. Within the context of my study this painting does not express the maternal warmth of the artist’s other maternities. Yet if it does succeed it is in the strength of the artist’s depiction of all aspects of motherhood. We have seen maternity's joys; this is its expression in bereavement. In 1789 on the night the monarchs were taken prisoner by Revolutionary crowds, the artist fled France with her daughter. Her marriage had not been successful, and her husband appropriated her substantial professional income to support his notorious gambling habit.40 Her memoirs state that, “In 1789 when I quitted France, I had not ... twenty francs, although I had earned more than a million. He had squandered it all.” He would not be joining them in exile. Now a single mother, the artist kept her daughter by her side, instead of installing her in a convent for her education as was then common among their social class (and indeed had been the artist's own fate). Schooled by private tutors, Julie grew into a lovely and accomplished woman |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Marie-Antoinette with Her Children, 1787. Oil on canvas, Chateau de Versailles, Versailles, France. |

|

Having fled France, Vigée Le Brun’s artistic reputation gained her invitations to the highest courts in Europe. She and Julie spent their first three years in Italy where she painted over thirty portraits of the nobility in Rome, Naples and Turin.41 In Vienna over the next three years she completed over fifty portraits42 including this one: Madame de Schöenfeld with her Child (1793).43 The rich russet and green silks in the mother’s gown and headdress enrich the warmth of the pair’s embrace. I particularly enjoy the emphasis on affectionate touch in this portrait: The mother’s cheek nuzzles against her daughter’s forehead, her right hand enfolds her daughter while her left caresses her sweet bare foot, while the daughter’s right hand extends to rest on her mother’s neck, or perhaps play with the beads of her necklace. These attributes invest this portrait with true maternal intimacy and are given further evidence in the cheerful expressions of both subjects. In Vienna the artist also painted portraits of members of the Russian Strogonoff family, who would then invite her on to Russia. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Countess von Schöenfeld, 1793. Oil on canvas. (Mme. Scöenfeld, wife of Saxon Minister) |

|

The artist would eventually spend six years in St. Petersburg and Moscow, completing around sixty portraits of the Russian nobility.44 This maternity of the Baroness Anna Strogonova and her son Sergey displays the tenderness evident between the pair, the mother’s hands tenderly enfolding her son, whose plump little hand extends to caress his mother’s neck. Again, this emotional warmth is magnified by the rich apricot tones of the mother’s dress, and the exotic detailing of the fabrics in which she is draped. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Baroness Anna Stroganova and Her Son Sergey, 1795. Oil on canvas, 90.5 x 73 cm, Stroganov Palace Museum, Leningrad. |

|

Another almost identical composition is seen in the maternity of Princess Alexandra Golitsyna and her Son, (1794). One can see that once the artist had refined effective ways to illustrate the joys of motherhood, she repeated them prolifically: mother and child are wrapped in affectionate embrace with skin-to-skin contact, soft lighting illuminates the rosy plump skin of the infant and the pure complexions of the mother, and always rich fabrics in warm gorgeous tones infer the emotional warmth between the figures. Although the artist would be allowed to return to France in 1801 after twelve years of exile, she found conditions there so changed, and so many of her friends having been executed by the guillotine, that she left France to spend another three years in England. Here she would complete another 30 portraits, including the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV, and Lord Byron. Despite Rousseau’s social reforms and contributions to the Enlightenment, he has come under fire by feminist scholars who consider his identification of motherhood as women’s highest calling, as barely-disguised misogyny 46 and a step backward for feminine independence.47 Aspects of Rousseau’s personal life do not bear close scrutiny. Of the five illegitimate children he fathered with his seamstress (whom he did later marry), he consigned all to anonymity in a foundling hospital, where they were essentially raised as orphans.48 Conditions in foundling hospitals at the time were notorious, with mortality rates of the abandoned children often reaching 90 percent.49 When his critics discovered he had abandoned his children, it seriously undermined the force of his reforms, and in his memoirs he expressed regret over what he claimed he had no other choice. Rousseau’s shortcomings to his own children may be somewhat alleviated by considering the no doubt thousands of infants whose lives his reforms saved. |

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Portrait of Princess Alexandra Golitsyna and her Son, 1794. Oil on canvas. 137 x 101 cm. Inv. No 1227. |

|

Despite forging a path for female artists within a male-dominated profession, Vigée Le Brun has equally suffered under the sharpened pens of art historians and feminist scholars, who regard her art as objectifying women in the most stereotypical role of domesticity.45 While I agree that her maternity paintings did become formulaic, and therefore may or may not accurately record the degree of engaged motherhood in her subjects' actual lives, their significance in addressing critical issues of her generation can be lost when viewed from the vantage point of later centuries. Feminist critiques look only to how her art might have affected prospects for women's equality, yet very little is said on behalf of the children, for whom reforms were desperately needed and for whom Vigée Le Brun's images of women re-claiming primary roles in mothering illustrated the direct solution. Given the artist’s embodiment of Rousseau’s ideals, I was disappointed to not find in her memoirs any direct commentary on his reforms or discourses on motherhood. However because Rousseau's writings influenced the French Revolution and the subsequent death of her friends and royal patrons (in whom her allegiance never wavered), it is not surprising that she would avoid textual reference of him directly. For evidence of her affinity with his ideals, we are left instead with the embodiment of maternal investment expressed both in her paintings and in her passionate devotion to her daughter Julie. |

Firmin Baes (1874-1945, Belgian), Sweet Dreams (Doux rêves), 1897-1945. Pastel, 52.1 x 63.5 cm. |

|

Fortunately Vigée Le Brun is regaining a higher regard in the art world, as art historians such as Mary Sheriff, Lesley Walker and Gita May have re-examined her art and contributions in a new and more generous light. Few other women artists have achieved such an illustrious career, or a more adventurous life travelling the length and breadth of Europe painting its most noble citizens. In her 87 years she completed over 900 works of art and broke new ground for female artists and future depictions of motherhood, such as these two final maternities from the nineteenth-century Belgian artist Firmin Baes, and the twentieth-century American artist Mary Cassatt. (Considering that Cassatt spent most of her working life in France, it is not unlikely that her style was influenced by viewing the maternity paintings of Vigée Le Brun in Paris, which so enriched the genre two centuries earlier.49) I believe these works of art express a debt to Vigée Le Brun for her innovations in the eighteenth century, unveiling maternal intimacy and indeed promoting its expression both on and off the canvas. As the French historian Lesley Walker said of the artist’s maternities, “In the same way that ‘liberty’ and ‘equality’ were thought to be universal principles that all men shared, so ‘maternity,’ too, comes to be understood as an ideal unifying all humanity.”50 |

Mary Cassatt, Mother Nursing her Baby, c. 1908. Oil on canvas, 39 5/8 x 32 1/8 in, Art Institute of Chicago. |

| |

|

Entire text (including endnotes but without images) in Document PDF form here. |

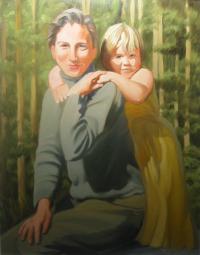

And just for fun, here is my modern maternity portrait by my father!: |

Art History papers:

- Dutch Illuminations: The Courtyard Paintings of Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684)

- Maternity Portraiture by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun: How Eighteenth-Century Art Mirrored Changing Paradigms in Child-rearing Practices