Dutch Illuminations:

The Courtyard Paintings of Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684)

(History of Art undergraduate paper, by Holly Cecil)

|

Click on any image to enlarge: Pieter de Hooch's genre paintings of sunlit households document realistic domestic architecture, embody ideals of feminine virtue, and illuminate the intimate lifestyles of seventeenth-century Dutch citizens for the modern viewer. In this essay I examine his painting Courtyard of a House in Delft (see Figure 1), a deceptively simple scene but one rich with insight into the private lives and homes of Dutch citizens in this period. Simon Schama's analysis of the private and public facets of Dutch culture in his treatise, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age, unlocks layers of meaning embedded in de Hooch's artistic compositions. I also complement Schama's research with additional works examining women's roles in child-rearing and maintaining domestic food-stores, the gendered division of Dutch interiors, and the architectural constraints in the nation's coastal towns unique to building on land reclaimed from the sea. Comparative imagery is drawn from genre paintings by de Hooch's contemporaries such as Frans Hals and Johannes Vermeer. In this essay I will show that de Hooch re-created truthful depictions of feminine culture in the Dutch Republic, which celebrated not only the worth of domestic virtue within the larger community, but also the simple beauty of lives being quietly lived. I begin with de Hooch's Courtyard of a House in Delft, completed in 1658, which invites the viewer into a private sunlit courtyard adjacent to a Delft townhouse. A young girl and a woman are shown to the right, while to the left, a well-dressed woman stands with her back to us at a doorway opening onto the street. This setting is consistent with many of de Hooch's works in which he extends feminine domestic space, normally considered the interior of the home, into a courtyard where mothers, children and servants are shown either socializing or busy at household tasks, such as laundry, cleaning fish, or spinning. Unlike the populated and chaotic joviality of genre paintings by the artist's contemporary Jan Steen, de Hooch instead portrays characteristically quiet scenes, created through common elements of only two to three figures and spartan settings. We believe in them because they are anchored in geometric living spaces created with perspectival verisimilitude, reminiscent of the Delft architectural painters Gerard Houckgeest, Emanuel de Witte and Carel Fabritius. Within his three-dimensional spaces de Hooch positions figures and objects sparingly in key positions, achieving levels of embedded symbolism.1 His interiors and courtyards come alive due to his mastery in portraying the wash of light into sequential spaces: sunlit courtyards contrasting shaded corridors, clean tiled interiors illuminated by sunbeams, and doorways open to reveal the world beyond. |

Figure 1: Pieter de Hooch, Courtyard of a House in Delft, 1658, oil on canvas, 73 x 60 cm (28.7 x 23.6 in), the National Gallery, London. |

|

|

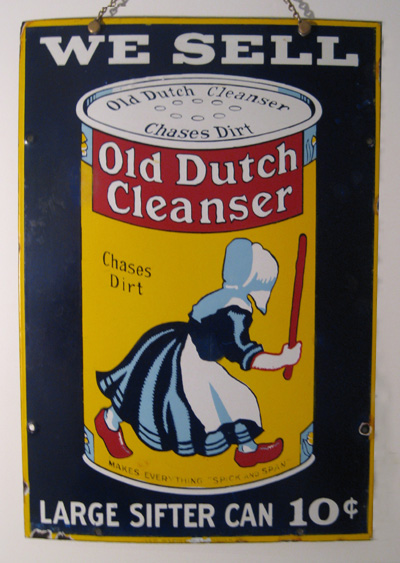

In The Embarrassment of Riches, Schama identifies cleanliness as a virtue revered by Dutch citizens, and that seventeenth-century travellers to the Netherlands consistently marvelled at the pristine condition of the cities and homes they encountered there. First-hand accounts document the near-spotless city streets, paved with bricks and apparently so clean that women could walk in open mules without soiling their stockings—rare indeed when most European cities still ran with sewage and refuse.2 This may reflect the fact that the Dutch Republic held the highest standard of living in Europe until the latter part of the eighteenth century.3 Inside the home, cleaning regimens cycled through a rota of tasks which ensured that every corner of the house could always be found in immaculate condition. This reverence for cleanliness was a tenet of Dutch Calvinism, in which spiritual purity was exemplified in the moral and physical purity of a well-ordered household. Adherence to scripture was enacted in daily, weekly, and seasonal cleaning tasks orchestrated by popular household manuals, such as The Experienced and Knowledgeable Hollands Householder. Contemporary didactic and satirical literature alike rendered the image of the Dutch cleaning woman iconic,4 such as the seventeenth-century De Beurs der Vrouwen (The Stock Exchange of Women), from which Schama quotes: “‘These womenfolk, neat and clean from without, mop and scrub, wash and scour and polish and wipe all the walls, the beams, and the pillars that hold the building up. While their hearts and souls shine from their ardor for this work ... for the impure heart can never be freed from dirt.’”5 This iconography praising the virtue of Dutch cleanliness and its symbolism has persisted to the present day, for example in the household cleaning product Old Dutch Cleanser, whose logo features a Dutch woman in traditional cap and clogs, chasing after dirt below the trademark, “Old Dutch Cleanser chases dirt, makes everything spick and span.” This drive for personal purity through scrubbing clean their houses also extended to their nation. Schama recounts the contemporary moralist writer Roemer Visscher, in whose popular emblem book, Sinnepoppen, the legend “afkomst seyt niet— pedigree counts for nothing” is paired with the image of the scrubbing brush. In the new Dutch Republic, the old format of inherited allegiance is scrubbed away and replaced by a new commonwealth, bearing the brush as its heraldic device to cleanse the nation of past impurities.6 |

Figure 2: Old Dutch Cleanser |

|

|

De Hooch's Courtyard of a House in Delft bears witness to the Dutch reverence for immaculate domestic spaces, particularly in Delft where the industries of beer-brewing and cheese-making required immaculate environments. Even in this private courtyard, not only secluded from the street but also containing some rather rustic-looking outdoor structures, the household's cleaning regimen has prevailed, as evidenced by the spotless brick terrace and the cleaning bucket and broom in the foreground. Indeed, most of de Hooch's paintings from his Delft period, as well as those by his contemporaries Hendrick van der Burch and Pieter Jannsens Elinga, feature the virtuous image of either a maid sweeping or a broom prominently displayed. If this terrace has so evidently already been cleaned, why are the broom and bucket not put away but instead left lying in the foreground? De Hooch orchestrated his paintings by positioning selected elements with great care; perhaps the broom and bucket are so placed in order to draw our eye to the fascinating pattern and the cleanliness of the courtyard bricks beneath them, which emphasize that in this household, domestic order is complete. |

Figure 3: Detail, Woman and Maid in a Courtyard, c.1660. |

|

|

The Dutch virtue of cleanliness extended not only to their cities and homes, but also to their persons. The women and child in de Hooch's courtyard are simply but immaculately clothed, the linen of their caps and aprons clean and straight. We may surmise that the care and rigorous attention that they applied to the surfaces of their home were equally applied to their own attire and grooming. Another of de Hooch's paintings which illustrates Schama's theme of domestic virtue is A Mother's Duty (see Figure 4), a tender scene of a mother combing through her child's hair, to keep it clean from lice. This process required the use of an extremely fine-toothed comb, which not only removed the lice but also any nits (eggs) which might in time hatch out in the hair. In The Embarrassment of Riches, Schama reproduces an image of a lice comb which originally appeared in Roemer Visscher's Sinnepoppen, paired with the emblem “Purgat et ornat” (to cleanse and adorn).7 The domestic virtue symbolized by maternal de-lousing was an emblem employed by de Hooch and also his contemporary Gerard ter Borch (Family of the Stone Grinder, 1652-53, and A Mother Combing the Hair of Her Child, 1653, also known as 'Hunting for Lice').8 De-lousing hair was an unpleasant and time-consuming process, a passage of time which I believe de Hooch alludes to in this painting by the long diagonal angle of sunlight pouring through the open half-door to bathe the clean tile floor in a brilliant trapezoid of light. Its importance is emphasized by the small dog in the foreground whose attention is riveted on this light. We are therefore drawn to also watch it, and perhaps to imagine this illumination slowly advancing across the gleaming tiles in the passage of time as the mother patiently combs her child's hair. The warmth of her devotion is echoed in this sunlight and in the brass bed-warmer which hangs on the box-bed behind her. Paintings featuring a succession of light-filled architectural spaces, in which mothers, children and servants enact virtuous domestic themes, became de Hooch's métier—particularly in the decade he resided in Delft, having moved there from his native Rotterdam in 1654. In an analysis of the artist's ouevre the scholar Wayne Franits identifies de Hooch's characteristic views into successive chambers with the Dutch term doorsien, or “see through.”9 De Hooch used this technique in both interior and exterior scenes; in Courtyard of a House in Delft we see it in the sequence of full light on the foreground bricks, contrasting the quieter shade of the covered tiled passageway, and the open door to the sunlit street beyond. In An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art, Martha Hollander compares the compositional framework of de Hooch's paintings with those of his contemporaries Emanuel de Witte and Ludolf Leendertsz de Jongh, all showing deep perspectival domestic views. She found that among more than 160 paintings attributed to de Hooch, only twelve do not exhibit this technique of a doorsien revealing secondary and tertiary views to other rooms, courtyards or the street beyond.10 His productivity in this genre reflects a shifting preference among the northern Netherlands' art market from Catholic paintings depicting Biblical narratives to artwork characterized by brilliantly-lit perspectival scenes embodying spiritual values in daily life.11 |

Figure 4: Pieter de Hooch, A Mother's Duty (also known as Interior with a Mother Delousing her Child's Hair), c. 1658-60. |

|

|

De Hooch's celebration of the courtyard within his compositions highlights this setting's unique role in seventeenth-century Dutch homes. In Art & Home: Dutch Interiors in the Age of Rembrandt, Mariët Westermann explains the architectural constraints of building upon land reclaimed from the sea, resulting in the prevalence of contiguous canal-fronted houses with narrow façades in coastal towns such as Amsterdam, Leiden and Delft.12 Construction on soft, drained soil required builders to sink supporting pilings down an astonishing twenty metres just to reach solid ground.13 Expensive square-footage in house footprints meant that architects designed homes to be built upward rather than outward. Westermann recounts that narrow houses often reached five or six stories tall, meticulously documented in the engravings by artist and firefighter Jan van der Heyden, such as Sectional View of a House on Fire in Amsterdam and Ruins After a Fire (see Figure 5). Schama contrasts Dutch canal towns with their European contemporaries such as Venice, where the palazzi were oriented laterally with their widest façade parallel to the canal. Houses in canal towns such as Amsterdam were instead laid out perpendicularly to the canal, with civic constraints specifying a narrow frontage of approximately thirty feet against a depth of one hundred and ninety feet.14 Dutch row houses featured wide banks of windows at the front and rear, (precluded from side walls which adjoined their neighbours), both to maximize light and to literally lighten the weight of the buildings to prevent their sinking into the reclaimed soil. A secondary house (achterhuis) was often constructed at the rear for cooking, separated from the main house by the airy courtyard which admitted light to both buildings.15 The importance of the courtyard within the overall design, as a near-weightless extension to the living space, cannot be underestimated within Dutch vernacular architecture. |

Figure 5: Jan Van der Heyden, Ruins After a Fire |

|

|

Another de Hooch painting which faithfully depicts a Delft courtyard and its outbuildings is Woman and Her Maid in a Courtyard (see Figure 6). The mistress of the house, identified by her fur-trimmed coat, supervises her maid who is cleaning a fish at the water-pump.16 Beside the maid is a black cooking pot in which the fish will be cooked for the family meal. De Hooch paints all the components of a contemporary courtyard; I particularly enjoy the lovely grey fashioned water-pump casing,17 from which the pump-handle extends vertically downward. The design of this pump was faithfully reproduced for the courtyard of the painter Johannes Vermeer for the 2003 award-winning film Girl with a Pearl Earring. De Hooch also paints the stone basin below the pump; the outbuildings in the rear of the courtyard; the ubiquitous cleaning broom and bucket in the foreground; and the shallow drainage channel which runs diagonally across the composition and divides the maid from her mistress. This channel originates under the outbuilding at right, which may be a kitchen or dairy room for making cheese. Philips Vingboon's domestic architectural designs, which date from the 1630s to the mid-1670s, affirm the authenticity of de Hooch's Delft courtyards (see Figure 6). Typical components were the front voorhuis, separated from the rear achterhuis by an open courtyard, and a covered corridor which connected them, such as the one seen in our primary painting.18 The courtyard, or binnenhoff, gave access to supplementary outbuildings including an outhouse or secreten, and the kitchen, sometimes in the rear achterhuis.19 Given de Hooch's architectural authenticity, can we glean any meaning as to the actions of the woman and child in our primary painting? It is possible that they have been visiting the secreten (privy), as the rustic door atop the steps beside them hints at this location.20 In Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden Age, the authors confirm that houses in this period did not enjoy the advantage of indoor plumbing, and that the privies or secreten were located either adjacent to the house's exterior walls or within courtyard outbuildings.21 The woman beside the girl carries a bowl which might contain water for hand-washing, correlating to the girl's gesture which might be interpreted as drying her hand on her apron. Yet why might they go to the trouble of carrying water when the household water-pump would have been only steps away within the courtyard? |

Figure 6: Pieter de Hooch, Woman and Maid in a Courtyard, c.1660. |

|

|

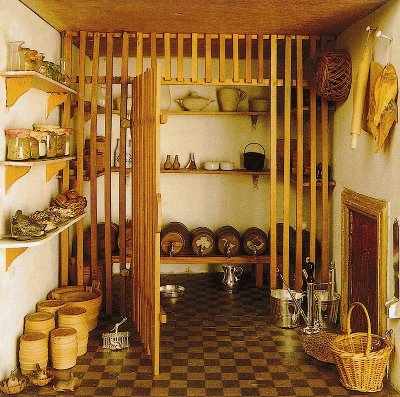

Although reading their position as exiting a privy is plausible, it represents rather an indelicate subject for a painting. I believe a more meaningful explanation is that they have instead been in a food store-room, a topic which reveals fascinating insight into Dutch food-storage innovations. In The Embarrassment of Riches, Schama reports the great availability and affordability of fresh fruit and vegetable produce within the Dutch Republic, due to advanced horticulture in its many provinces and the network of trade canals which connected them.22 Not only were the Dutch adept at agriculture, but also in food storage innovations which kept their produce fresh over the long winter months. Kegs of wine and beer, cheeses, and preserves in glass or porcelain jars were stored in interior house cellars, and this very inventory is faithfully replicated in the storage room within the contemporary Dollhouse of Petronella Dunois, ca. 1676 (see Figure 7).23 If households were dependant on a stocked supply of the summer's proliferation of produce, why are fruits and vegetables not also replicated in the dollhouse cellar? The Dutch knew that in order for fruits and vegetables to retain their freshness, they must be stored at cooler temperatures and a higher humidity than those afforded by house storage. A further deterrent to indoor storage was the knowledge that over time, root vegetables can give off unhealthy gases. A composite solution was the innovation of a root cellar, or “Dutch cellar” as it became known among contemporary immigrants to North America, an insulated and often subterranean outbuilding in which produce remained fresh yet unfrozen in extreme climates. A further solution was to bury the vegetables in barrels of sand in these cellars, which absorbed unhealthy gases and maintained a low air temperature.24 |

Figure 7: Cellar Detail of Dollhouse of Petronella Dunois, c.1676. |

|

| Might de Hooch's woman and child be exiting a produce-storage outbuilding? The girl holds her apron in a way which might serve to carry fruit, yet the woman does not appear to carry any produce. One answer might be that some vegetable preserves, such as sauerkraut made from cabbage, require periodic skimming of their brine to remove any surface molds which might have developed on them. Another explanation might be that this is a dairy cellar or buttery, for the rinds of hard cheeses likewise require periodic wiping with brine to prevent against mold. Either of these readings might explain the woman's purpose and the bowl she carries. Having personal experience in the fading arts of maintaining root cellars and making cheeses, batches of wine, preserves, and sauerkraut, as this woman might also have, gives me a feeling of personal connection to these figures. Within this reading, the understanding of architectural segregation for the production and storage of Dutch foodstuffs gives de Hooch's Courtyard of a House in Delft a meaningful realism. The tender visual interchange between the woman and child who hold hands, introduces yet another theme from The Embarrassment of Riches, that of affectionate and permissive approaches to child-rearing in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic. Schama relates contemporary accounts by foreign visitors who disapproved of Dutch parents for being far too indulgent towards their young and giving what they saw as unprecedented and unwarranted physical displays of affection.25 Yet to modern eyes these very parents appear to have led the way out of restrictive methods of child-rearing then common in Europe. If contemporary family portraits and genre scenes can be taken as evidence, the Dutch abandonment of harmful practices such as restrictive swaddling and abandoning infants to wet-nurses resulted in happier, healthier, more affectionate families. Such advancements would not be enjoyed by other western European countries for over a century, when instigated by social revolutionaries such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Schama also asserts that to the Dutch, the family home superceded any other educational environment for the molding of their offspring. Everyday tasks became the training-ground for young virtuous citizens and to further Calvinist values of moral and practical discipline. The Dutch genre scholar Wayne Franits also confirms that to Protestants, the strength of the nation rested on the foundations of the home, and that families were considered kleyne kercken (little churches), dedicated to morality based on scripture and to raising pious offspring.26 |

Figure 8: Pieter de Hooch, Courtyard of a House in Delft (detail), 1658, the National Gallery, London. |

|

| Genre scenes from this period, such as de Hooch's Woman Peeling Apples (see Figure 9), show younger children either observing or participating in the household work of their elders.27 In this painting a young girl assists her mother in preparing apples for the family meal, taking the ribbon-like peel discarded from her mother's hand. She is not yet ready to wield her mother's knife, but is entrusted with the secondary task of receiving the finished peeled apples and placing them in the bowl at her mother's feet. This transference of household skill between generations is sensitively depicted in this quiet interior scene, the two figures bathed in a soft light emanating through the window from the right. Mothers and children preparing food appear in other genre paintings such as de Hooch's Woman Preparing Vegetables with a Child, 1657 (also called Interior of a Dutch House) and Nicolas Maes's Maid Peeling Parsnips. Their choice of food preparation to symbolize education can be explained by Schama's revelation: “Opvoeding, the word for education, was, after all, etymologically rooted in the verb voeden, to nourish or feed, and if learning was supposed to nourish virtue, nourishment was supposed to be a form of learning itself.”28 Genre paintings depicting food preparation as a symbol of virtuous education strengthens the reading of the woman and child in Courtyard of a House in Delft as having been caring for food-stores in their outbuildings, representing the many facets of Dutch domestic life in child-rearing, education, and the preservation of food-stores. Another theme addressed by Schama is the gendered division of work and habitational space in the Dutch Republic. Contemporary house-plans differentiated between the more public or masculine ground-floor front of the house, where business was conducted and patrons received, and the rear and upper rooms that were reserved for domestic activities such as cooking and entertaining friends and family. These demarcations are also verified by Irene Cieraad in “Dutch Windows: Female Virtue and Female Vice” in At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space.29 New concerns of privacy and gender division in this period were evolving out of existing European households with larger communal domestic rooms. Likewise, the rejection of Catholic themes in art production in the Dutch Republic opened the way for the emergence of new genres, and thus the re-ordering and gendering of domestic space began to be represented in art. |

Figure 9: Pieter de Hooch, Woman Peeling Apples, c. 1663. |

|

Cieraad cites the popularity of household manuals—such as Jacob Cats's Houwelyck (Marriage), with approximately fifty thousand copies in print by 1650—and that their policies guiding women in domestic virtue were created exclusively by male writers and artists.30 To balance this, Schama lauds the engravings of domestic hardship by the female artist Geertruid Roghman as being unique among art production in that period and indeed until the nineteenth century. He admits that they could only have been made by a woman personally experienced in the hard physical reality of household work.31 Her descriptive Kitchen Interior (see Figure 10), illustrates the many cooking pots and implements used in the preparation of food, and further reminds us of stacks of dishes waiting to be washed. Engaged in the ardour of her work, the subject remains oblivious to the viewer as she prepares a dish with either pastry or cheesecloth on the cooking surface. The verisimilitude of her gendered space is not dissimilar to de Hooch's courtyards and their women, in both a faithfulness to domestic chores and the ordered environment in which they are enacted. Neither are de Hooch's women relieved of their domestic burdens, yet contrasted with Roghman's solitary worker they face the viewer as if to include us in their experience. De Hooch's scenes, particularly those including children, exude an atmosphere of contentment in shared work. Of central importance to de Hooch's ouevre is that many of his compositions extend the demarcation of feminine domestic space into the courtyard. In An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art, author Martha Hollander asserts that de Hooch was the first artist to use the courtyard as a setting for domestic scenes, and that in Dutch culture this space became an outdoor counterpart to the inner domestic environment.32 Schama corroborates this identification of the courtyard as a uniquely Dutch extension of the house interior, domestic and feminine in nature. He notes that this contrasted with other European cultures such as the Venetians whose houses secreted their female members “behind latticed windows, inaccessible balconies, massive gateways or the masks of their favourite entertainments.”33 While not yet emancipated, Dutch women nevertheless enjoyed greater economic and social freedoms than their European sisters, a fact perhaps symbolized in de Hooch's paintings by domestic space being extended outdoors and literally into the light of day. A third scholar, Walter Liedtke, likewise affirms that de Hooch may be said to have painted “outdoor living rooms, not public spaces.”34 |

Figure 10: Geertruid Roghman, Kitchen Interior, engraving c.1648-50. |

|

|

De Hooch's A Courtyard in Delft at Evening: A Woman Spinning, beautifully affirms this unique outdoor extension of domestic space (see Figure 11). It is late in the day, and the lady of the house has been spinning out-of-doors to take advantage of the last of the sunlight. We have seen that architectural constraints in canal-towns such as Delft resulted in house interiors receiving limited light, through windows at the front and rear only, therefore impelling their inhabitants outdoors for better light to work by. The woman's back is to us, but the quality of her dress identifies her as the mistress of the house, while the second woman can be recognized as her serving-maid from the simple clothing and apron that she wears. The maid has filled earthenware jugs at the water pump, and is carrying them back toward the house. Although differentiated in dress, the two women both share in the diligence of household tasks, expressing an egalitarianism of gendered work in Dutch culture. What visually most impresses me in this painting are the two glorious trapezoids of sunlight on the courtyard dirt which I believe de Hooch uses to create meaning, not unlike the sunlight marking the passage of time across the floor tiles in A Mother's Duty. In this courtyard the sunlight celebrates the unrestricted freedom and warmth of the outdoors, while its contrasting shadows—cast by the house—perhaps represent their opposite of indoor seclusion and privacy. The women's tasks are not confined indoors but instead are released into the fresh air and light of day. By including the Delft rooftops in the background, de Hooch seems to set the value of their work within the visible context of their larger community. I believe it is not insignificant that the two women inhabit a position in the courtyard which spans these two seeming contrasts of dark and light, indoor domesticity and outdoor civic worth. |

Figure 11: Pieter de Hooch, A Courtyard in Delft at Evening: A Woman Spinning, c. 1657. |

|

|

In transferring their domestic tasks out of doors, de Hooch could not have chosen a more feminine symbol than spinning. The distaff used to spin fibres is also the term used to denote the maternal branch of the family tree: the “distaff” or feminine side. Its counterpart is the symbol of the spear, ascribed to the paternal or masculine branch of the family tree. Might de Hooch have deliberately chosen this symbol of femininity in his painting to create a worthy counterpart to contemporary civic militia paintings, such as Frans Hals's Archers of Saint Adrian (1633), in which raised spears, symbols of masculinity, figure prominently? (See Figure 12.) If so he would not have been alone in asserting the worth of women within Dutch culture. In 1639 the Dordrecht physician Dr. Johan van Beverwijck published a treatise on the excellence of the female sex, in which he praised woman's accomplishments and the fortitude with which they met life's challenges: “To those who argue ... that women are fit only to manage the house and no more, I reply that many women go from the home and practice trade and the arts and learning. Only let woman come to the exercise of other matters and they will show that they are capable of all things.”35 De Hooch's many gendered domestic compositions may be seen to directly illustrate van Beverwijck's assertion that the governing and organizing skills required to run a household were not unlike those needed to rule a city or state.36 |

Figure 12: Frans Hals, Archers of Saint Hadrian, c. 1633. |

|

|

Returning to our primary painting, what can we tell about the woman by the doorway whose back is to us? In De Hooch's compositions of sequential geometric spaces, he often placed a figure at a open doorway to draw the viewer's eye toward the outdoor space it revealed. Because of her gaze we look past her into the street and to the house opposite, but nothing more can be seen. Is she waiting for someone? I believe her isolation illustrates the solitary condition of many Dutch women in this period. Merchants travelling to distant cities, and men employed by the navy or the Dutch East and West India Companies, were often away from their families for months or years at a time. Among all other countries in the world, the Dutch Republic claimed the highest percentage of men whose work took them away from their homes, either trading or in the navy, fishing and whaling industries.37 Many of them would never return. No doubt due to tropical diseases and hardships at sea, for most of the seventeenth century fully two-thirds of men sent to Asia with the Dutch East India Company died there.38 It was a harsh reality that for many women in the Dutch Republic, such as de Hooch's woman who waits by the doorway, their men might never return home. An analysis of Pieter de Hooch's paintings would not be complete without celebrating the range of tiles, bricks and flagstones he arranges in tessellated patterns on the surfaces of his household flooring and walls. The painter came by it honestly; he was born in 1629 to a Rotterdam stonemason and brick-layer, and would no doubt have been exposed to these crafts through his father's work. His move to Delft in 1656 further exposed him to the virtuosity of perspectival artwork by the resident architecture painters Fabritius, Houckgeest and de Witte already noted. From this point in his career, de Hooch's paintings evolved from simplistic tavern scenes to meticulously-crafted and innovatively-lit domestic environments. Their perspectival realism relied on the geometric grid-work of innovative patterns fashioned in the brick- and tile-work of floors and wall-skirting.39 |

Figure 13: Pieter de Hooch, Courtyard of a House in Delft, (detail) 1658, oil on Canvas, 73 x 60 cm (28.7 x 23.6 in), the National Gallery, London. |

|

|

Our primary painting reveals a catalogue of building materials: due to a lack of building stone, Dutch houses were usually constructed of brick, which gave a visual warmth to their exteriors. The brick has also been laid in interesting contrasting horizontal bands on the vertical facade supporting the archway. In the corridor, the sunlit figure of the solitary woman reflects off the Delft blue and white wall-tiles to her left. Delft faience and tile fabrication was central to the town's prosperity, valued not only within the Dutch Republic but also in other countries such as England where they were imported to decorate home interiors. Although they are not displayed prominently beside de Hooch's woman in the passageway, Delft tiles figure widely in others of his paintings—such as those flanking the hearth in Woman Peeling Apples (Figure 9) and behind the wicker basket in A Mother's Duty (Figure 4). These tiles featured miniature painted scenes of children's games, and served more than a decorative purpose; in the damp Dutch climate they were an affordable way for householders to cover and protect the lower half of interior walls.40 |

Figure 14: Delft Wall Tiles |

|

|

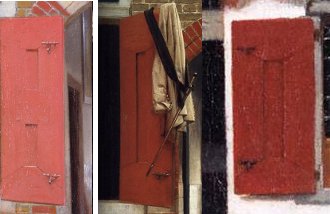

De Hooch often reproduced the same views in different paintings, as may be seen in a near-replica completed in the same year, Figures Drinking in a Courtyard, 1658 (see Figure 15). In this composition he has retained the prominent construction of the house and passageway to the left, but replaced the solitary woman with a girl and puppy who sit on the stone step. The street glimpsed through the open doorway now reveals a canal running down its length. To the right of the composition the painter removed the woman, girl and outbuildings. The trellis remains but has been re-worked into a sturdier construction to support the vine. Below it a women and two men socialize at an outdoor table over a glass of wine, a mug of beer, and a smoked pipe. The composition may have changed but the same air of contented order remains. Another noticeable difference is that the painter has fabricated a new foreground, diagonally alternating squares of flagstones with brick-work to create a pleasing geometrical flourish. This indicates that de Hooch possessed an extensive working knowledge of perspectival interiors, exteriors, and human elements. Duplicated paintings suggest that he did not paint literal transcriptions but instead synthesized household elements into carefully orchestrated composites to achieve a desired effect.41 A final example of this orchestration can be seen in the red shutter of the house, at the left of both courtyard paintings. The chromatic strength of the shutter anchors the viewer within both compositions, lending a visual and emotional warmth. |

Figure 15: Pieter de Hooch, Figures Drinking in a Courtyard, 1658. |

|

|

This feature calls to mind my final comparative image, The Little Street by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), (see Figure 16). The row-houses in canal-towns possessed façades similar to their neighbours; even so, this perspective could possibly be identified as the view of de Hooch's courtyard and house, as seen from a vantage point across the street. Inside the same passageway we now see a woman bending over a barrel, beside the ubiquitous emblem of the cleaning broom. We also see the front view of the house, where two children are engrossed in a game, and an elderly woman is sewing in the doorway. The artist Vermeer, like his Delft contemporary de Hooch only three years his senior, is loved for his sensitive depictions of women in domestic interiors. This painting is rare for the reason that it is one of only two exteriors known to have been painted by him; the other is his unforgettable townscape View of Delft. Both artists are considered by the Delft scholar Walter Liedtke to have influenced each other rather equally, and their friendly rivalry may be evidenced in the remarkable similarity of paintings such as de Hooch's Woman Weighing Coins and Vermeer's Woman Holding a Balance.42 |

Fig. 16: Johannes Vermeer, 'The Little Street' (also known as View of Houses in Delft), c. 1658. |

|

I see their connection not only in the similarity of the architecture here depicted by both artists, but specifically in the red shutter of Vermeer's house, which never fails to be mentioned by scholars when analyzing this painting for the critically important visual and chromatic anchor it provides. Close examination reveals that its design is identical in the artists' three paintings (Figures 1, 15 and 16): a wide frame with a narrow interior recess, bearing two bolts which secure it from the interior when shut, and all painted the same tone of rich, warm brick-red. I see this shared shutter as a symbol of the artists' undocumented mutual inspiration. De Hooch's sensitive portrayals of modest Delft households are limited to the decade he resided in that artistic crucible. After his move to Amsterdam in 1663 his upscale interiors with marble floors and gilt-leather wall coverings reflect a wealthier class of patrons and no longer feature humble serving maids and rough outbuildings in rear courtyards. Yet through it all he excelled at depicting the brilliant effects of sunlight, streaming through open doors and windows, illuminating symmetrical domestic spaces, and making the floor tiles gleam. His mise-en-scènes of household tasks celebrate the simple but noble qualities of domestic virtue and the moral education of children, and overall an unprecedented valuing of feminine lives previously ignored by artists.43 Always there are permeable borders between gendered space and its broader civic setting shown through an open door to the wider world, which is welcoming and sets their work within the important context of the town and nation. De Hooch's end would come in 1684, in an Amsterdam insane asylum, but I prefer to remember him for the brilliancy with which he preserved the intimacy of Dutch domestic life. |

Fig. 17: Comparison (L to R) of the shutters in de Hooch's Courtyard of a House in Delft (1658), Figures Drinking in a Courtyard (1658),and Vermeer's, The Little Street, c. 1658. |

|

Entire text (including endnotes but without images) in Document PDF form here. BIBLIOGRAPHY:

|

||

Art History papers:

Back to Main Paintings PageAbout the ArtistArtist’s StatementGreat Britain page |

||