Great Britain Page

Click on any image to view in larger format

all photos by Holly Cecil except where noted

|

Since my first visit to Great Britain in 1981, I have been captivated by the many layers of history embedded in the land. This seeems most powerful at ancient sites such as stone circles, standing stones, and burial mounds which date from the Neolithic period (roughly 4,000-8,000 years ago). The massive menhirs of Stonehenge (right), composed mainly of quartz, made a big impression on me, especially being able to view them up close which is no longer allowed the general public. Nearby is Avebury Circle, inside of which the town of Avebury has slowly grown up, in part by reclaiming some of the massive stones for building materials in the anti-pagan Victorian era. Other magical sites in the British Isles are Callanish Stone Circle on the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. This seems to me to be a more ‘feminine’ version of Stonehenge. The tall stones seem to stretch up to connect the land to the endless sky, and they are beautifully swirled with textures and colours of mixed components. The fact that most of these neolithic monuments were aligned astronomically is best evident in Newgrange, Ireland. At right is shown the entrance to the long passageway leading to the inner burial chamber. In a masterful feat of engineering, the square opening above the doorway allows a shaft of light to penetrate the inner chamber during the Winter Solstice of each year. Neolithic chambered tombs exist throughout the British Isles, such as Lanyon Quoit in Cornwall which is estimated to be 5,000-6,000 years old. Many of these tombs would have been covered with a mound of turf or earth, making them a dolmen. Another magical site in Cornwall is Men-an-Tol, with its feminine circle stone. Folk superstition holds that if a child suffering from rickets was passed naked through the centre of the stone three times, they would be cured. Other rituals included ‘handfasting’ where a couple would plight their troth by holding hands through the hole in the stone. The countryside itself seems to breathe this otherworldly charm, especially at certain times of the year such as May Day, when bluebells appear in a profusion of colour in the deciduous forests. One of my favourite trees is the beech tree, tall, elegant and sinuously graceful. The tall beech tree pictured here lives on the hill above our town where we used to live, Hay-on-Wye on the border of Wales. The crown of beech trees pictured to the right of it was discovered by friends Danny and Kate near Moreton-in-Marsh. A ring of tall beech trees, their roots intertwined, circle a single, masculine cypress tree. A perfect spot for a tryst or a conspiracy, I’d guess! In closing I must aknowledge Nicky and Charly Martin, Carole Brown, Danny Blyth and Kate Newman for sharing with Anthony and I the magical sites around Great Britain! |

|

Stonehenge, England, 1998 |

Holly at Stonehenge, 1995 Photo by Rodger Hyodo |

Don Berger and Holly at Avebury Stone Circle Photo by Ethel Valiant |

Callanish Stone Circle, Scotland Photo by Carole Berger |

Entrance to Newgrange, Ireland Photo by Nicky Martin |

Lanyon Quoit, Cornwall |

Men-an-Tol, Cornwall |

Bluebells, Cornwall forest |

Beech tree, Hay-on-Wye, Wales |

Crown of Beech Trees, Gloucestershire, England |

Recommended Reading:

- ‘The View Over Atlantis’ by John Michell (Ballantine Books, 1969)

- ‘The Old Straight Track’ by Alfred Watkins (Abacus/Sphere Books Ltd., 1976)

- ‘The Romance of the Stones: Cornwall’s Pagan Past’ by Robin Payne (Alexander Associates, 1999)

ReDiscovering the Ancient Yew

by Holly Cecil

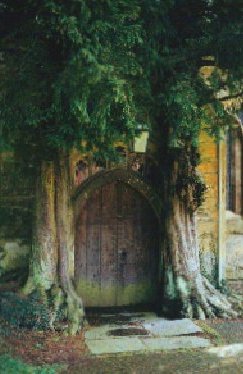

In the heart of towns and villages in the British Isles lies an ancient treasure. Long shackled with misunderstanding and tarnished from superstition, it has persevered through centuries--further adding to its mystique of immortality. Within the last decade, work has at last begun to restore this treasure to its proper place of veneration and celebration within our communities. If you stroll through any local churchyard, you will most likely discover it: the yew tree. The two trees pictured here guard the door of the church at Stow-on-the-Wold.

Due to the visionary work of Allen Meredith, among others, the process for determining the age of yews has undergone a radical transformation, revealing ancients in our midst. Because aging yews eventually rot at the centre and become hollow, it has been difficult to use traditional ring counting techniques to date them. Based on a vision that their life span is much longer than previously believed, Allen set about researching documented yew trees in historical church and village records. His methods have now been accepted by the establishment, and endorsed by such notables as Alan Mitchell and Sir George Trevelyan. Churchyard yews that were formerly thought to be only centuries old have now been placed at 2,000 to 4,000 years--a venerable age. But how did they come to pre-date the churches beside them?

The answer lies in the reverence humans have always displayed for trees. In early childhood they beckon to us to climb their lofty boughs, as lovers we meet beneath their shady bowers, and in later years we simply revel in the beauty and artistry of their graceful stature amid the landscape. In early Britain trees were venerated on sacred mounds, at hallowed springs and other sites for thousands of years. With the coming of Christianity, these sites were co-opted into the new religion, and chapels and cathedrals were built over the old meeting places. Trees have always captured our imagination as powerful symbols of regenerative life. How fitting then that we should re-discover the yew as a tangible link to a time when humans were much more in tune with nature, at this point in our history when we have almost destroyed it.

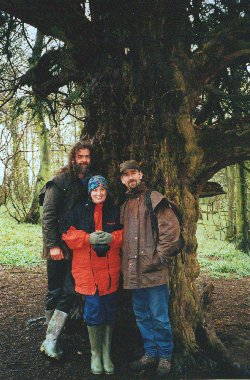

To see yews growing wild beyond

the bound of churchyards is to appreciate their true

character. In forests such as Kingley Vale (near

Chichester, Sussex) or at Odstock (near Salisbury), are

magnificent yew groves which have spread from perhaps a

single tree. The tree pictured here is one of many on

Wychbury Hill, near Birmingham. The yew’s lower

limbs naturally grow out and downward, and where that

limb eventually roots in the soil, another tree will grow

up from it. Therefore one observes almost concentric

rings of trees, although sometimes it is difficult to

tell which is the parent and which is the offspring! The

aging yew will eventually become hollow or split, but

that does not presage its doom. Often it will send an

aerial root down its hollow centre (a perfect example is

the churchyard yew at Linton, near Ross-on-Wye), to

further nourish and stabilise its bulk. In this way a yew

can continue healthy, if somewhat gnarled, for

centuries.

To see yews growing wild beyond

the bound of churchyards is to appreciate their true

character. In forests such as Kingley Vale (near

Chichester, Sussex) or at Odstock (near Salisbury), are

magnificent yew groves which have spread from perhaps a

single tree. The tree pictured here is one of many on

Wychbury Hill, near Birmingham. The yew’s lower

limbs naturally grow out and downward, and where that

limb eventually roots in the soil, another tree will grow

up from it. Therefore one observes almost concentric

rings of trees, although sometimes it is difficult to

tell which is the parent and which is the offspring! The

aging yew will eventually become hollow or split, but

that does not presage its doom. Often it will send an

aerial root down its hollow centre (a perfect example is

the churchyard yew at Linton, near Ross-on-Wye), to

further nourish and stabilise its bulk. In this way a yew

can continue healthy, if somewhat gnarled, for

centuries.

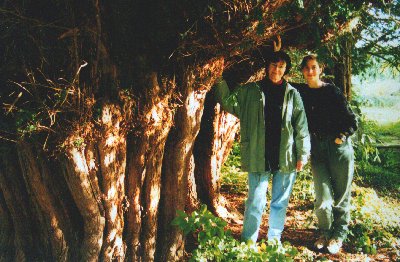

Another beautiful quality of yews are the enigmatic patterns which form in their plum-red and moss-green bark. As new layers are continually growing over old, swirling and twisting around boughs and crevices, they form what look to the eye as uninhibited, sensual body shapes--a generous belly here, an arching back there, all flowing together in a symmetry of pleasure. When I first viewed this in a wild yew, I thought my imagination had quite run astray! However after questioning my fellows, they all admitted to identical interpretations. It seems that there are playful and earthy spirits inhabiting these trees, or perhaps they reflect back to us what our humanness once was before we adopted dispassionate civility. It is interesting to note that churchyard yews are much more ‘toned down’ in this respect--perhaps out of deference to Victorian churchgoers they grew smoother and less suggestive bark than their wilder cousins, so as not to offend passers-by on a Sunday morning!

The rigours many churchyard yews have undergone at the hands of well-meaning parishioners were sadly due to lack of knowledge at the time. During the last few centuries, yews which became hollow in their natural process of growth were used as a store for coal or rubbish, or bricked up in an attempt to preserve their stability--which ironically prevented the aerial root from taking its regenerative course. Also, iron bands were placed around the trunk in an attempt to stop the natural ‘horizontal spread.’ Sprawling lower limbs were lopped off, preventing not only the yew’s inclination to parent new trees but more importantly to stabilise itself. In such a trussed-up and vulnerable state, many ancient yews became the victims of windstorms they would have otherwise endured. Happily, most yews now grow uninhibited, their revised age and status celebrated by a certificate in the nearby church for all to see (part of the ongoing campaign to raise awareness).

This gorgeous matriarch is a female yew tree in Cusop Churchyard, Herefordshire, estimated to be a venerable 2,000 years old. As we are faced with impending environmental crises arising from our alienation with nature, it is ironic that we have re-discovered the immortal yew at this very time. There is perhaps no finer symbol for regeneration and renewal than these unstoppable trees. Perhaps most of all, they can teach us that we will live in harmony with nature only when we cease striving to improve on her more subtle wisdom.

Artist's Statement

About the Artist

Back to Paintings Page